Who We are

Years ago I met kids from Bombay’s Victoria Terminus, now called the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus. They were drug addicts who eked out an existence by stealing, conning and `reserving’ seats in unreserved compartments by securing them. They did so by sitting on them when the train was in the yard and giving it up for passengers who were willing to pay a price. Some others collected empty bottles and goods left or forgotten by passengers and sold them. The money made was deposited in a `bank’ — a paan-beedi shop in Central Mumbai — which charged a monthly fee for keeping the money. There was no locker but there was trust which could be broken anytime.

Demanding life

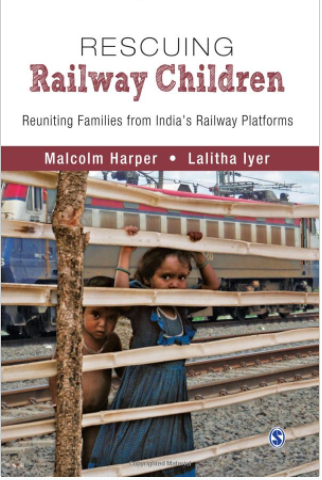

The story of such runaway children is ridden with many complexities. It is not a uniform experience with any definitive pattern. The common thread is that those who chose to make the platform their abode are those who decided to leave home. Approximately 80,000 of them arrive on platforms in India every year. Some of them are also those lost or left behind in the human melee and thus separated from their parents.

Life on the railway platform is obviously demanding and difficult. There are many heartbreaking stories on the 64,460 km of route length that the Indian Railways covers across the length and breadth of the country. But trying to capture the light through the cracks and restore hope is what Sathi (Society for Assistance to Children in Difficult Situation), a 27-year-old organisation, has made its mission. It tries to get as many runaway children as possible back on the track they belong — their families.